Thoughts on Government Applicable to the Present State of the American Colonies

by John Adams

| Thoughts on Government | ||

at the College of William & Mary. |

||

| Author | John Adams | |

| Published | Boston: John Gill | |

| Date | 1776 | |

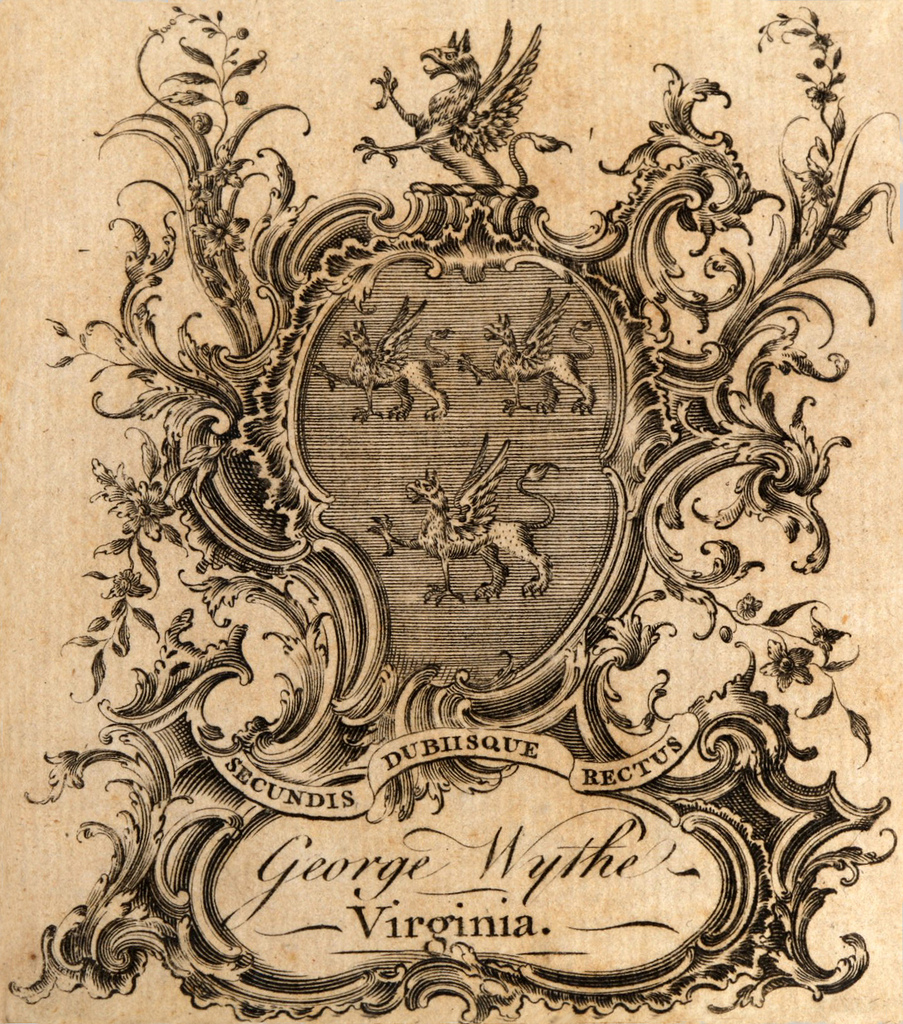

John Adams was the second President of the United States (1797-1801) as well as the first first Vice President of the United States under George Washington (1789 -1797). Adams was a Founding Father who served on two Continental Congresses, championed American independence from Britain, and later held a long career as diplomat to France, Great Britain, and the Netherlands. His work Thoughts on Government, written for George Wythe, was influential for its ideas regarding separation of powers and checks and balances.

Adams was born in Braintree, Massachusetts in 1735, to Deacon John Adams and his wife Susanna.[1] He attended Harvard College[2] and would eventually practice law in Boston, entering the company of prominent lawyers like Jeremiah Gridley and James Otis, Jr.[3]. He married Abigail Adams (née) Smith in 1764 [4] and although they were often separated, the two of them maintained a frequent correspondence, with Adams entrusting her with responsibilities and independence far beyond what was typical for the time. [5]

When the Boston Massacre occurred in 1770, Adams successfully defended the British soldiers, motivated by the idea that all men are entitled to a fair trial.[6] He served as a delegate from Massachusetts on the first Continental Congress in 1774 [7] and then on the second Continental Congress in 1775.[8]. While serving on the Second Continental Congress he sat on ninety committees, chairing twenty-five, leading Benjamin Rush to describe him as “the first man in the House.”[9] Adams even maintained that he was offered the role of drafting the Declaration of Independence, but he declined and deferred it to Thomas Jefferson instead, though Jefferson claimed he was the original, and only, choice. [10] These disputes were a hallmark of their relationship, which consisted both of friendship [11] and rivalry. [12] With Jefferson head of the Democrat-Republicans and Adams a Federalist, they ran against each other in the 1796 presidential election, resulting in Adams's victory, with Jefferson serving as vice president.[13]

Before becoming president, Adams had a long diplomatic career, beginning in 1777 when he was selected to replace Silas Deane as a diplomat to France, serving alongside Benjamin Franklin and Arthur Lee.[14] Afterwards, he was reassigned as diplomat to the Netherlands in 1780[15] and then the First American Minister to Great Britain after the end of the Revolutionary Way in 1785.[16] Upon his return from Europe in 1789, Adams was elected the first Vice President of the United States, serving under the first President, George Washington.[17] Adams would later become the second President of the United States, during which he oversaw the passing of the Alien and Sedition Acts,[18]) navigated a potential war with France[19], and became the first president to live in the White House.[20] After his presidency he returned to Massachusetts, where he would start up a correspondence with Thomas Jefferson consisting of one hundred and nine letters sent by Adams and forty-nine by Jefferson[21] lasting until they both died on the same day — July 4th, 1826.[22]

Evidence for Inclusion in Wythe's Library

The John D. Rockefeller, Jr. Library at Colonial Williamsburg owns a copy of the printed version of Adams's letter to Wythe with the following catalog description, 'Library's copy signed on title page: "John Adams to George Wythe" in Adams' hand. Several textual corrections and the date "January 1776" also by Adams.'[23] This could mean that John Adams presented this copy to George Wythe, or it could be a reference by Adams to note which version of the letter he used for publication.[24] Both Brown's Bibliography[25] and George Wythe's Library[26] on LibraryThing include Adams's tract in Wythe's library based on the copy at Colonial Williamsburg. While this copy may not have been Wythe's, it is highly likely he owned a copy of the published version of Adams's essay.

The Wolf Law Library has been unable to locate a copy for purchase.

See also

References

- ↑ John Ferling, John Adams : A Life (New York: Henry Holt & Co., 1996) 11.

- ↑ Ferling, John Adams, 15

- ↑ Ferling, John Adams, 23-24

- ↑ Ferling, John Adams, 34

- ↑ Ferling, John Adams, 172

- ↑ Ferling, John Adams, 67-68

- ↑ Ferling, John Adams, 97

- ↑ Ferling, John Adams, 121

- ↑ Peter Shaw, The Character of John Adams, (Chapel Hill: Published for the Institute of Early American History and Culture, Williamsburg, Va., by the University of North Carolina Press, 1976) 95

- ↑ Robert McGlone, “Deciphering Memory: John Adams and the Authorship of the Declaration of Independence,” Journal of American History 85, no. 2 (1998): 411.

- ↑ Ferling, John Adams, 273.

- ↑ Ferling, John Adams, 314.

- ↑ Ferling, John Adams, 332.

- ↑ Ferling, John Adams, 198.

- ↑ Ferling, John Adams, 229.

- ↑ Ferling, John Adams, 274.

- ↑ Ferling, John Adams, 299.

- ↑ Ferling, John Adams, 365.

- ↑ Ferling, John Adams, 378.

- ↑ Ferling, John Adams, 395.

- ↑ Brooke Allen, “John Adams: Realist of the Revolution,” The Hudson Review 55, no. 1 (2002): 48, https://doi.org/10.2307/3852843.

- ↑ Ferling, John Adams, 444.

- ↑ John Adams, 'Thoughts on Government: Applicable to the Present State of the American colonies. In a Letter from a Gentleman to His Friend' (Boston: John Gill, 1776), https://catalog.libraries.wm.edu/permalink/01COWM_INST/oaj29m/alma991023672029703196.

- ↑ "Thoughts on Government [Editorial Note,"] Founders Online, National Archives, accessed August 28, 2025.

- ↑ Bennie Brown, "The Library of George Wythe of Williamsburg and Richmond," (unpublished manuscript, 2009, rev. 2023) Microsoft Word document (on file at the Wolf Law Library, William & Mary Law School).

- ↑ LibraryThing, s.v. "Member: George Wythe," accessed on August 28, 2025.