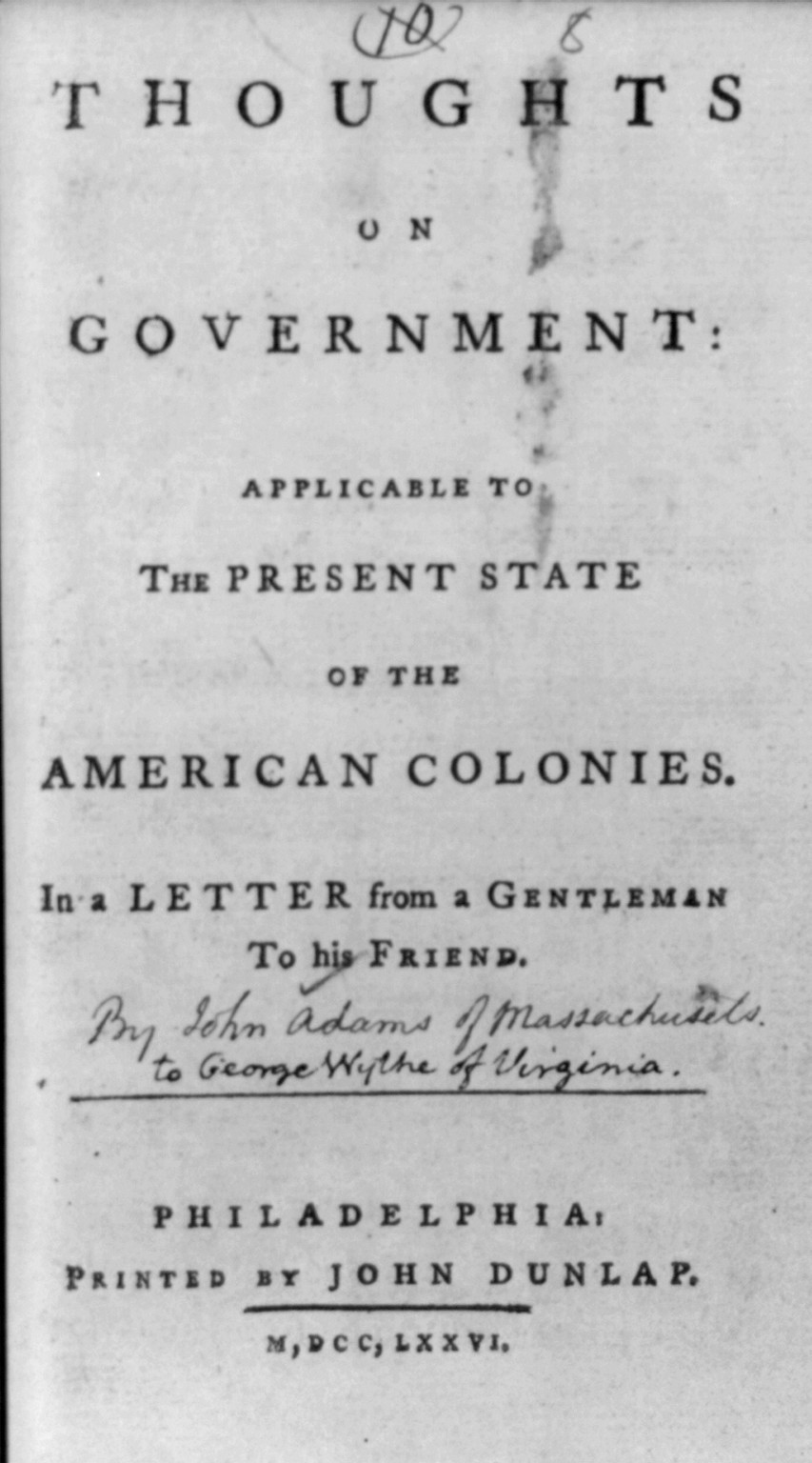

Thoughts on Government Applicable to the Present State of the American Colonies

by John Adams

| Thoughts on Government | ||

at the College of William & Mary. |

||

| Author | John Adams | |

| Published | Boston: John Gill | |

| Date | 1776 | |

John Adams was the second President of the United States (1797-1801) as well as the first first Vice President of the United States under George Washington (1789-1797). Born in was born in Braintree, Massachusetts in 1735,[1] Adams was a Founding Father who served on two Continental Congresses, championed American independence from Britain, and later held a long career as diplomat to France, Great Britain, and the Netherlands. He attended Harvard College[2] and would eventually practice law in Boston, entering the company of prominent lawyers like Jeremiah Gridley and James Otis, Jr.[3] He married Abigail Adams (née Smith) in 1764 [4] and although they were often separated, the two of them maintained a frequent correspondence, with Adams entrusting her with responsibilities and independence far beyond what was typical for the time. [5]

When the Boston Massacre occurred in 1770, Adams successfully defended the British soldiers accused of shooting into the crowd, motivated by the idea that all men are entitled to a fair trial.[6] He served as a delegate from Massachusetts on the first Continental Congress in 1774 [7] and then on the second Continental Congress in 1775.[8]. While serving on the Second Continental Congress he sat on ninety committees and chaired twenty-five, leading Benjamin Rush to describe him as "the first man in the House."[9] Adams maintained that he was offered the role of drafting the Declaration of Independence, but he declined and deferred it to Thomas Jefferson instead, though Jefferson claimed he was the original, and only, choice. [10] These disputes were a hallmark of their relationship, which consisted both of friendship [11] and rivalry. [12] With Jefferson head of the Democrat-Republicans and Adams a Federalist, they ran against each other in the 1796 presidential election, resulting in Adams's victory and Jefferson serving as his vice president.[13]

Before becoming president, Adams had a long diplomatic career, beginning in 1777 when he was selected to replace Silas Deane as a diplomat to France, serving alongside Benjamin Franklin and Arthur Lee.[14] Afterwards, he was reassigned as diplomat to the Netherlands in 1780[15] and then the First American Minister to Great Britain after the end of the Revolutionary Way in 1785.[16] Upon his return from Europe in 1789, Adams was elected the first Vice President of the United States, serving under the first President, George Washington.[17] Adams would later become the second President of the United States, during which he oversaw the passing of the Alien and Sedition Acts,[18] navigated a potential war with France[19], and became the first president to live in the White House.[20] After his presidency he returned to Massachusetts, where he would start up a correspondence with Thomas Jefferson (consisting of one hundred and nine letters from Adams and forty-nine from Jefferson).[21] They two of them remained in contact until they both died on the same day — July 4th, 1826.[22]

Thoughts on Government

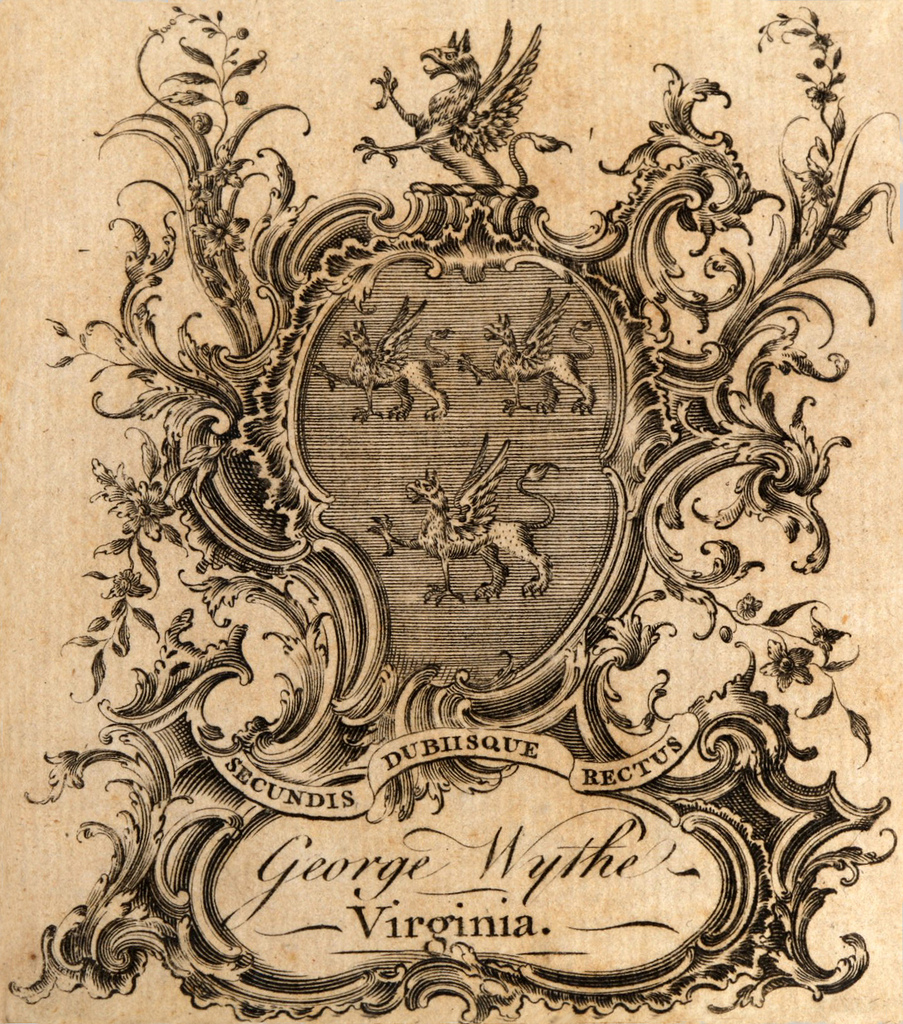

Adams frequently contemplated matters of governance, including in letters which he sent to at least four of his colleagues: William Hooper, John Penn, Jonathan Dickinson Sergeant, and George Wythe.[23] There is some debate over which copy of Thoughts on Government was written first. Some believe it was originally written for George Wythe[24] when he sought Adams’s help in drafting a new constitution for Virginia in 1776. Adams responded that they had "a fair opportunity to form and establish the wisest and happiest government that human wisdom can contrive"[25] and the resulting document was George Wythe's copy of Thoughts on Government. Adams would also later recount in letters to Benjamin Rush[26] and Mercy Otis Warren[27] that it had been written originally for Wythe. Edmund Jenings also referred to it as "your Epistle to Mr. Wythe" in a letter to Adams.[28] However, it is possible that these claims are a result of Adams's imperfect memory, as there is evidence showing the copies to Hooper and Penn were written first, with Wythe's being reproduced later by Adams almost entirely from memory.[29] Regardless of which version came first, it was Wythe's copy that would eventually be printed by Richard Henry Lee in April 1776 as the first publication of Thoughts on Government.[30]

According to Adams, the primary purpose of the government was to promote happiness amongst its citizens, and Adams thought this could be best accomplished by a bicameral legislature, as opposed to the unicameral legislature suggested by Thomas Paine earlier, which Adams fiercely opposed.[31] In fact, Adam's biographer, Peter Shaw, suggested that Thoughts on Government was written for Southerners with an aversion to Paine.[32] It was intended to nudge Southerners away from choosing hereditary monarchies for themselves by lauding the virtues of republicanism.[33] Ultimately, many states would adopt Adam's framework in Thoughts on Government in their new constitutions established after the Declaration of Independence, including suggestions such as veto powers for the executive and checks and balances on different branches of government.[34] For example, Virginia, North Carolina, and New Jersey were all influenced by Thoughts on Government in some form while drafting their constitutions.[35] Nowhere is this influence more clear, however, than in the Massachusetts Constitution of 1780, which Adams himself helped draft.[36] The framework set out in Thoughts on Government would also eventually be adopted in large part by the U.S. Constitution.[37]

Evidence for Inclusion in Wythe's Library

The John D. Rockefeller, Jr. Library at Colonial Williamsburg owns a copy of the printed version of Adams's letter to Wythe with the following catalog description, 'Library's copy signed on title page: "John Adams to George Wythe" in Adams' hand. Several textual corrections and the date "January 1776" also by Adams.'[38] This could mean that John Adams presented this copy to George Wythe, or it could be a reference by Adams to note which version of the letter he used for publication.[39] Both Brown's Bibliography[40] and George Wythe's Library[41] on LibraryThing include Adams's tract in Wythe's library based on the copy at Colonial Williamsburg. While this copy may not have been Wythe's, it is highly likely he owned a copy of the published version of Adams's essay.

The Wolf Law Library has been unable to locate a copy for purchase.

See also

References

- ↑ John Ferling, John Adams : A Life (New York: Henry Holt & Co., 1996) 11.

- ↑ Ferling, John Adams, 15.

- ↑ Ferling, John Adams, 23-24.

- ↑ Ferling, John Adams, 34.

- ↑ Ferling, John Adams, 172.

- ↑ Ferling, John Adams, 67-68.

- ↑ Ferling, John Adams, 97.

- ↑ Ferling, John Adams, 121.

- ↑ Peter Shaw, The Character of John Adams, (Chapel Hill: Published for the Institute of Early American History and Culture, Williamsburg, Va., by the University of North Carolina Press, 1976) 95.

- ↑ Robert McGlone, "Deciphering Memory: John Adams and the Authorship of the Declaration of Independence," Journal of American History 85, no. 2 (1998): 411.

- ↑ Ferling, John Adams, 273.

- ↑ Ferling, John Adams, 314.

- ↑ Ferling, John Adams, 332.

- ↑ Ferling, John Adams, 198.

- ↑ Ferling, John Adams, 229.

- ↑ Ferling, John Adams, 274.

- ↑ Ferling, John Adams, 299.

- ↑ Ferling, John Adams, 365.

- ↑ Ferling, John Adams, 378.

- ↑ Ferling, John Adams, 395.

- ↑ Brooke Allen, "John Adams: Realist of the Revolution," The Hudson Review 55, no. 1 (2002): 48, https://doi.org/10.2307/3852843.

- ↑ Ferling, John Adams, 444.

- ↑ “[In Congress, Spring 1776, and Thomas Paine],” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/01-03-02-0016-0028. [Original source: The Adams Papers, Diary and Autobiography of John Adams, vol. 3, Diary, 1782–1804; Autobiography, Part One to October 1776, ed. L. H. Butterfield. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1961, pp. 330–335.]

- ↑ George C. Homans, "John Adams and the Constitution of Massachusetts," Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 125, no. 4 (1981): 287, http://www.jstor.org/stable/986331.

- ↑ Paul C. Reardon, "The Massachusetts Constitution Marks a Milestone," Publius 12, no. 1 (1982): 45, http://www.jstor.org/stable/3329672.

- ↑ “From John Adams to Benjamin Rush, 12 April 1809,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/99-02-02-5339.

- ↑ “From John Adams to Mercy Otis Warren, 11 July 1807,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/99-02-02-5193.

- ↑ “Edmund Jenings to John Adams, 29 June 1780,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/06-09-02-0288. [Original source: The Adams Papers, Papers of John Adams, vol. 9, March 1780 – July 1780, ed. Gregg L. Lint and Richard Alan Ryerson. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1996, pp. 489–490.]

- ↑ “Thoughts on Government [Editorial Note],” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/06-04-02-0026-0001. [Original source: The Adams Papers, Papers of John Adams, vol. 4, February–August 1776, ed. Robert J. Taylor. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1979, pp. 65–73.]

- ↑ Ferling, John Adams, 155.

- ↑ Ferling, John Adams, 155.

- ↑ Shaw, The Character of John Adams, 94.

- ↑ Shaw, The Character of John Adams, 92/3.

- ↑ Ferling, John Adams, 157.

- ↑ “Thoughts on Government [Editorial Note],” Founders Online.

- ↑ Reardon, "The Massachusetts Constitution," 51.

- ↑ Ferling, John Adams, 300.

- ↑ John Adams, 'Thoughts on Government: Applicable to the Present State of the American colonies. In a Letter from a Gentleman to His Friend' (Boston: John Gill, 1776), https://catalog.libraries.wm.edu/permalink/01COWM_INST/oaj29m/alma991023672029703196.

- ↑ "Thoughts on Government [Editorial Note,"] Founders Online, National Archives, accessed August 28, 2025.

- ↑ Bennie Brown, "The Library of George Wythe of Williamsburg and Richmond," (unpublished manuscript, 2009, rev. 2023) Microsoft Word document (on file at the Wolf Law Library, William & Mary Law School).

- ↑ LibraryThing, s.v. "Member: George Wythe," accessed on August 28, 2025.

External links

- Read this book online at the Massachusetts Historical Society.