Reports of Cases Adjudged in the Court of King's Bench, Since the Death of Lord Raymond

by James Burrow

| Burrow's Reports | ||

at the College of William & Mary. |

||

| Author | James Burrow | |

| Published | London: Printed by His Majesty's Law Printers for John Worrall | |

| Date | 1766-1780 | |

| Edition | First | |

| Language | English | |

Sir James Burrow (1701-1782) is considered the father of modern court reporting and the first commercially successful reporter of English law.[1] His influence led to the late 18th and early 19th centuries being considered the “great era of the court reporter.”[2] Born in Surrey in 1701, Burrow was a two-time president of the Royal Society and began his career privately recording the judgments of Chief Justice Lord Mansfield, whom he greatly admired.[3] While he did not originally intend to publish his reports, he would eventually do so after being subject to "'continual interruption and even persecution, by incessant applications for searches into my notes.'"[4] He and Mansfield had a close working relationship, and because many of Mansfield’s own records were destroyed by rioters in 1780, Burrow’s reports serve as good authority on the Chief Justice’s judgments.[5] In fact, the two were so close that at times it was suggested that Burrow’s reports on Mansfield’s judgments could not have been objectively prepared.[6]

Burrow is also the father of the modern headnote, which he formatted to contain few facts and always state a proposition of the law.[7] The following reports always included a statement of the facts, a summary of the arguments, and the court’s judgment — which is still the form of modern court reporting today.[8] His reports were not just functional but also considered “works of art.”[9] He also had an eye for reportability and omitted cases turning on facts or evidence only, stating that “‘I only report what I think may be of use as a determination or illusion of some matter of law.’”[10]

Reports of Cases Adjudged in the Court of King's Bench, Since the Death of Lord Raymond was published in three volumes between 1768 and 1777.[11] It was broken into four parts, one for each successor of Lord Raymond after his death in 1733, in the following order: Lord Hardwicke, Sir William Lee, Sir Dudley Ryder, and Lord Mansfield.[12] Burrow intended to work backwards from Mansfield's judgments in Reports of Cases,[13] so the first edition covered Mansfield's King’s Bench decisions from 1756 to 1761.[14] In the second volume, he attached a tract entitled “A few thoughts upon pointing,” (referring to punctuation).[15]

Evidence for Inclusion in Wythe's Library

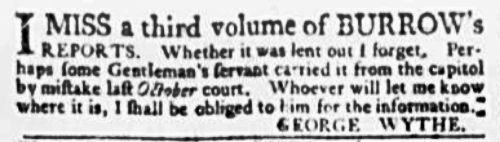

From the Virginia Gazette for February 7, 1771:

I MISS a third volume of BURROW's REPORTS. Whether it was lent out I forget. Perhaps some Gentleman's servant carried it from the capitol by mistake last October court. Whoever will let me know where it is, I shall be obliged to him for the information.

- GEORGE WYTHE.[16]

The notice ran for three weeks, from January 31 through February 14, 1771. In the first notice, the title was printed as "Barrow's" Reports. Wythe corrected the typesetter's error after the first week.

See also

References

- ↑ Michael Bryan, "Early English Law Reporting," University of Melbourne Collections 4, (2009), 48-50.

- ↑ Bryan, "Early English Law Reporting," 50.

- ↑ W. P. Courtney and David Ibbetson, "Burrow, Sir James (1701–1782), law reporter." Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. 23 Sep. 2004; Accessed 5 Nov. 2025. [1]

- ↑ Anthony Musson and Chantal Stebbings, eds. Making Legal History : Approaches and Methodologies, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012), 62. Accessed October 29, 2025. ProQuest Ebook Central.

- ↑ Paul D. Halliday, "Authority in the Archives," Critical Analysis of Law: An International & Interdisciplinary Law Review 1, no. 1 (2014): 111.

- ↑ James Oldham, “Eighteenth-Century Judges’ Notes: How They Explain, Correct and Enhance the Reports,” The American Journal of Legal History 31, no. 1 (1987): 13.[2]

- ↑ C.G. Moran, The Heralds of the Law, (Holmes Beach, Florida: Gaunt, 1996): 39.

- ↑ Michael Widener, "Landmarks of Law Reporting 10 -- Burrow's Reports: "Works of art"," Yale Law School Lillian Goldman Law Library, May 5th, 2009, https://library.law.yale.edu/news/landmarks-law-reporting-10-burrows-reports-works-art.

- ↑ Widener, "Landmarks of Law Reporting," (quoting John W. Wallace, from The Reporters Arranged and Characterized, 4th ed. (1882).)

- ↑ Moran, The Heralds, 39.

- ↑ Courtney and Ibbetson, "Burrow, Sir James."

- ↑ "Reports of cases adjudged in the Court of King's Bench, since the death of Lord Raymond; in four parts, ... By James Burrow ... 1771: Vol 1," Internet Archive, October 4, 2023, https://archive.org/details/bim_eighteenth-century_reports-of-cases-adjudge_great-britain-court-of-_1771_1.

- ↑ Moran, The Heralds, 37.

- ↑ Musson and Stebbings, Making Legal History, 54.

- ↑ Courtney and Ibbetson, "Burrow, Sir James."

- ↑ Virginia Gazette (Rind) January 31, 1771, 3; February 7, 1771, 4; and February 14, 1771, 4.