Nine Queries Concerning the Trinity, &c.: Proposed to the Hon. Emanuel Swedenborg by the Rev. Thomas Hartley with the Answers Given by the Former to Each Question

by Thomas Hartley and Emanuel Swedenborg

| Nine Queries Concerning the Trinity | ||

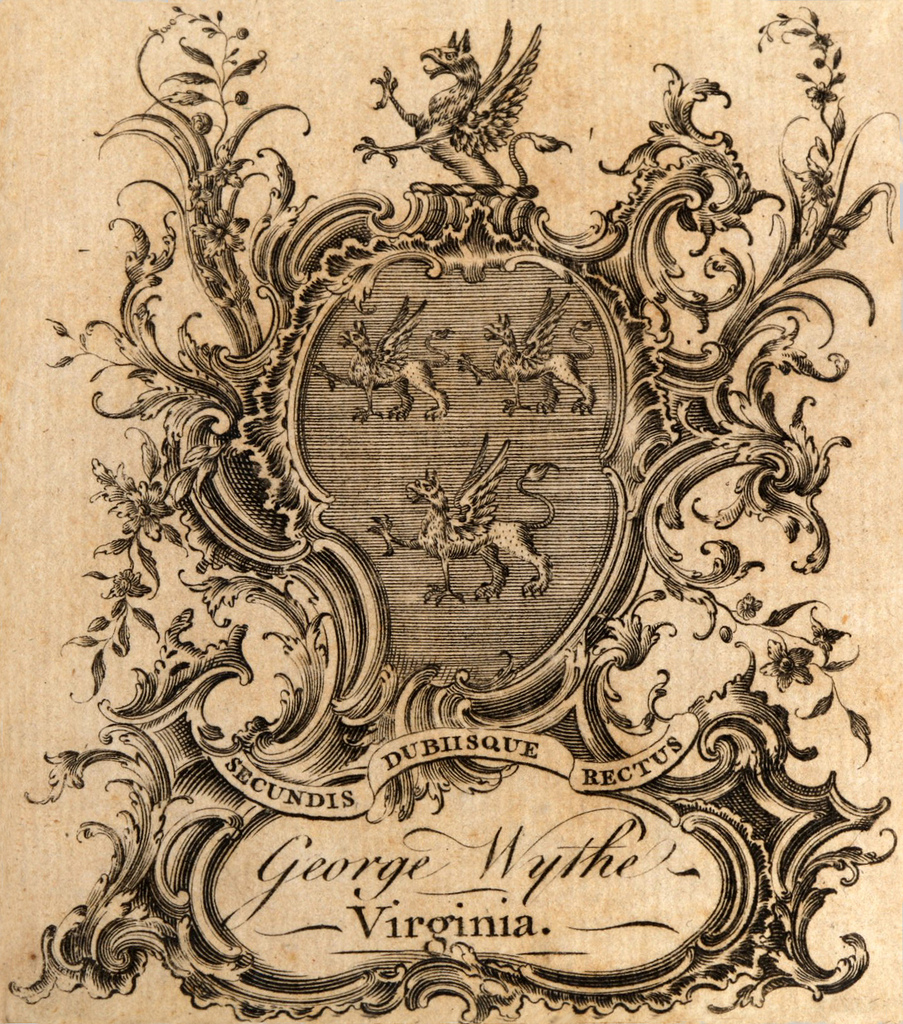

at the College of William & Mary. |

||

| Author | Thomas Hartley, Emanuel Swedenborg | |

| Translator | Robert Hindmarsh | |

| Published | London: R. Hindmarsh | |

| Date | 1786 or 1790 | |

| Language | English | |

| Desc. | Octavo | |

Emanuel Swedenborg (1688 – 1772) was a Swedish scientist and theologian. In the year 1719, his family was ennobled by the Swedish queen, and the family name changed from Swedberg to Swedenborg.[1] Following a prolific career in the natural sciences and engineering, Swedenborg began having religious visions. Modern scientists postulate that these episodes were the product of epileptic seizures.[2] Nonetheless, while he was always a spiritual person, these visions elicited a crisis which drove Swedenborg into a more mystical phase. During the last 28 years of his life, beginning at age 57, Swedenborg published 18 works on Christian theology, believing that Christ had appointed him to reform Christianity.[3]

Swedenborg was a divisive figure. While he undeniably possessed scientific prowess, he was only "grudgingly" recognized by the scientific world.[4] This could be because Swedenborg’s scientific thought cannot cleanly be separated from his mysticism.[5] Even those who respected elements of his scientific work often believed he was "otherwise a harmless lunatic."[6] Swedenborg’s religious work was also polarizing. He preached a theory of scripture that emphasized the senses and the hidden messages within biblical texts.[7] His ideas were entirely unique for his time.[8] Yet, while many categorize his contributions as eccentric and abnormal, Swedenborg's influence is found within the works of many respected intellectuals, including Balzac and Baudelaire.[9] Thus, while Swedenborg is recognized as "a central figure in the Western esoteric tradition; he was also crucial to much mainstream Western culture as well."[10]

Thomas Hartley (1709 – 1784) was a London born, Cambridge-educated reverend.[11] While he is best known for his association with Swedenborg, he also had an independent career, first as a curate at Chiswick, Middlesex, next as a vicar of East Claydon, Buckinghamshire, and then as the rector of Winwick, Northamptonshire.[12] Hartley published some sermons of his own and many translations of Swedenborg’s work.[13] Having a largely evangelical theological perspective at the start of his career, Hartley developed an interest in the ideas of mystics, such as Swedenborg, and actively advocated and defended their views.[14] He disputed the idea that mystics were unprincipled and "nonsensical."[15] His friendship with Swedenborg was particularly important to him. He even offered Swedenborg a place in his home in England if the mystic ever felt persecuted in his home country.[16] Still, Hartley’s association with Swedenborg brought him "outside organized society," and thus fundamentally structured the trajectory of his career.[17]

Nine Queries Concerning the Trinity, a translation of Quaestiones novem de Trinitate, &c., contains metaphysical questions asked by Hartley with answers provided by Swedenborg. Hartley's questions concern what God is, and how to understand the intersection of God and humanity. Swedenborg's answers rely heavily on his views on the Christian concept of the Trinity. Christianity typically understands the Trinity as the unity of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, but Swedenborg expands upon this concept to argue that the conventional elements of the Trinity are instead merely representative of another Trinity – God’s Divine Wisdom, Divine Love, and Quickening Spirit. Swedenborg argues that these three main qualities of God are then reproduced in humans through their minds, bodies, and souls.[18]

Swedenborg’s answers to Hartley’s questions do not necessarily rely on scripture or doctrine for validation. While he occasionally relates his arguments back to scripture, his theological approach is imprecise, and can be well described as having a "seraphic quality."[19] Instead of turning to doctrine, scripture, or precedent to build a case to prove and validate his views, "[h]e spoke with authority, less as an investigator than as a seer."[20] The basis for his views mainly relied on his own opinion, or upon "the natural instinct of the heart."[21] As a result, Swedenborg’s answers offer a view into his own personal spiritual interpretation and beliefs, more so than a doctrinal or scriptural view.

Evidence for Inclusion in Wythe's Library

A 1792 letter from Robert Carter to George Wythe is reprinted in an article by John Whitehead in a Swedenborgian newsletter, the New-Church Messenger (Chicago) from 1917, "The Early History of the New Church in America, VIII." In the letter, dated October 11, 1792, Carter states he is sending Wythe four volumes of Swedenborg's writings: Nine Queries Concerning the Trinity (1786, or 1790), A Short Account of the Honourable Emanuel Swedenborg and His Theological Writings, by Robert Hindmarsh (1792), The Liturgy of the New Church Signified by the New Jerusalem in the Revelation (1792), and the first volume of True Christian Religion, published in Philadelphia by Francis Bailey, 1789. Carter also mentions Swedenborg's A Treatise Concerning Heaven and Hell (London: W. Chalklen, 1789) being sold by a local merchant in Richmond:[22]

Under a particular Influence I present to you the following Books, viz., the first vol. of the True Christian Religion, 9 Questions concerning the Trinity proposed to E. S. by the Rev. Thos. Hartley, also, His Answers. A short account of the honorable E. S. and His Theological Writings, and the Liturgy of the New Jerusalem Church. The Liturgy is a Production arising from the Baron's Writings; for Societies are established in several of the most principal towns in Great Britain, styled members of the New Jerusalem Church, which was foretold was to be by the Lord, by the Prophet Daniel and the Evangelist John in the Revelation.

It is said that many copies of a Treatise on Heaven and Hell by E. S. were imported by a merchant of Richmond Town, which work communicates much comfort to Believers.

Wythe replied in October, 1792, thanking Carter for the books and stating, he wished "I had power to remunerate your beneficence by sending books to you which would do to you no less good than those handed to me by Mr. Dawson ought in your opinion to do to me."[23] Swedenborg's works do not appear in Thomas Jefferson's inventory of books received from Wythe's estate after his death in 1806. Wythe may not have kept the four books gifted from Carter, giving them away or otherwise disposing of them. To date, the Wolf Law Library has been unable to locate a copy of Nine Queries Concerning the Trinity.

See also

- The Liturgy of the New Church Signified by the New Jerusalem in the Revelation

- "The Early History of the New Church in America, VIII"

- Short Account of the Honourable Emanuel Swedenborg and His Theological Writings

- True Christian Religion: Containing the Universal Theology of the New Church

- Wythe to Robert Carter, 17 October 1792

- Wythe's Library

References

- ↑ Elizabeth Foote-Smith and Timothy J. Smith, “Emanuel Swedenborg,” Epilepsia 37, no. 2 (1996): 211.

- ↑ Foote-Smith and Smith, “Emanuel Swedenborg,” 212.

- ↑ Alexander James Grieve, "Swedenborg, Emanuel." Encyclopædia Britannica, vol. 26, Hugh Chisholm, ed. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1911), 221-223.

- ↑ O.B. Frothingham, "Swedenborg," The North American Review 134, no. 307, (1882): 600.

- ↑ Frothingham, "Swedenborg," 601.

- ↑ Frothingham, "Swedenborg," 601.

- ↑ Frothingham, "Swedenborg," 605.

- ↑ Frothingham, "Swedenborg," 604.

- ↑ Gary Lachman, Swedenborg: An Introduction to His Life and Ideas (Penguin, 2012), xvii.

- ↑ Lachman, Swedenborg, xvii.

- ↑ Alexander Gordon and Jon Mee, "Hartley, Thomas (1708/9-1784)," Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Accessed Sept 16, 2025.

- ↑ Gordon and Mee, "Hartley, Thomas (1708/9-1784)."

- ↑ Gordon and Mee, "Hartley, Thomas (1708/9-1784)."

- ↑ Gordon and Mee, "Hartley, Thomas (1708/9-1784)"; Ariel Hessayon, "Jacob Boehme, Emanuel Swedenborg and their readers," in In The Arms of Morpheus: Essays on Swedenborg and Mysticism, ed. Stephen McNeilly (London: Journal of the Swedenborg Society, 2007), 27.

- ↑ Hessayon, "Jacob Boehme, Swedenborg and their readers," 27.

- ↑ Geo. Trobridge, "Swedenborg in England," The New Century Review 6, no. 34 (1899): 321.

- ↑ Gordon and Mee, "Hartley, Thomas (1708/9-1784)."

- ↑ The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica, "Emanuel Swedenborg," Encyclopedia Britannica, May 1, 2025. Accessed September 12, 2025.

- ↑ Frothingham, "Swedenborg," 602.

- ↑ Frothingham, "Swedenborg," 601.

- ↑ Frothingham, "Swedenborg," 602.

- ↑ Robert Carter to George Wythe, October 11, 1792. Reprinted in John Whitehead, "The Early History of the New Church in America, VIII," New-Church Messenger (Chicago) 112, no. 10 (March 17, 1917), 186-187.

- ↑ George Wythe to Robert Carter, October 17, 1792, in Library & Archives, Maine Historical Society.