Archimedous tou Syrakousiou Psammites, kai Kyklou Metresis. Eutokiou Askalonitou eis Auten Hypomnema = Archimedis Syracusani Arenarius, et Dimensio Circuli. Eutocii Ascalonitæ, in hanc Commentarius

by Archimedes

| Archimedous tou Syrakousiou Psamites | ||

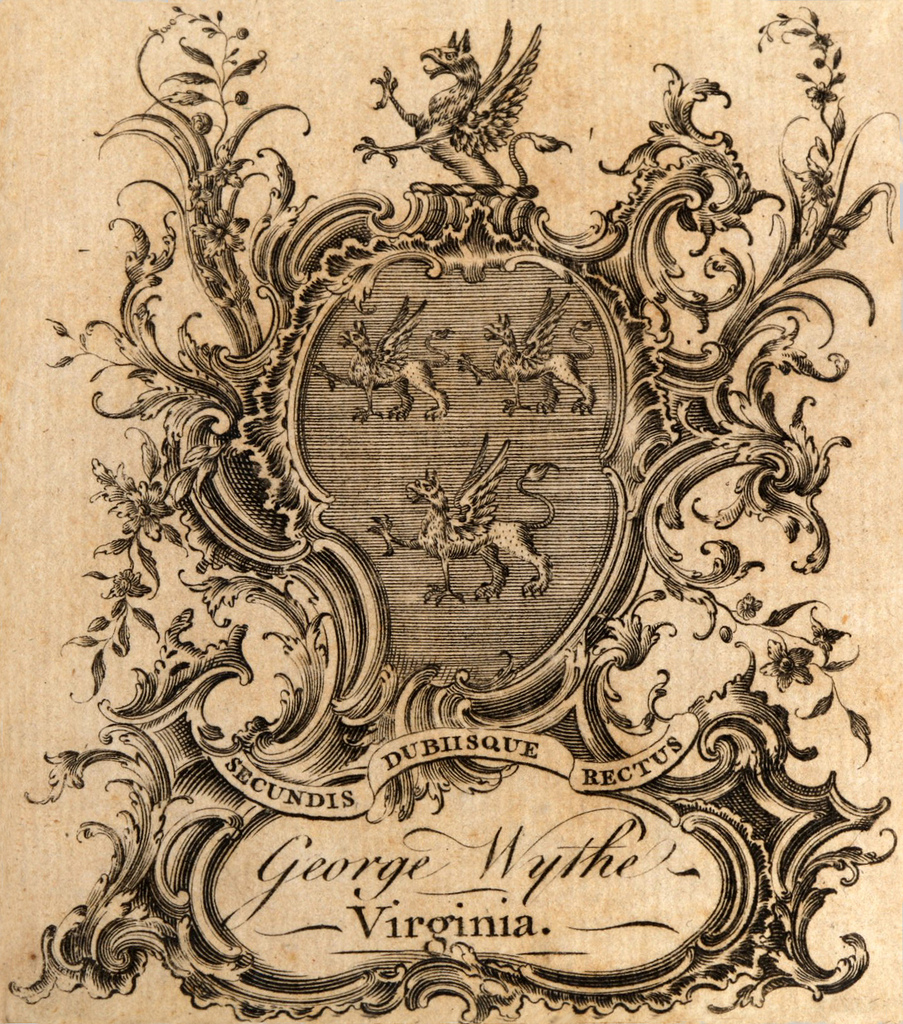

at the College of William & Mary. |

||

| Author | Archimedes | |

| Published | Oxonii: e Theatro Sheldoniano | |

| Date | 1676 | |

Archimedes was an Ancient Greek mathematician, scholar, and inventor known for his works in geometry, physics, and hydrostatics.[1] Scarce information exists regarding his early life, but based on the writings of twelfth-century historian Tzetzes, scholars believe Archimedes was born in 287 B.C.[2] in Syracuse, a city on the southern coast of Sicily.[3] He spent time in Egypt and maintained ties with other scholars in Alexandria, then known as the "centre of Greek science."[4] Archimedes performed numerous experiments including one in which he determined the amount of gold used in a wreath commissioned by King Hiero II (from which the famous phrase "Eureka!" derives).[5] Credited with a number of inventions such as the planetarium,[6] Archimedes gained fame for his war machines. These ranged from ballistic machines to ward off the invading Romans[7] to a supposed "heat ray" made using burning mirrors (the likelihood of which is still debated in the modern day).[8] He died in 212 B.C. during the Roman invasion of Syracuse, killed while drawing diagrams in the sand by a Roman soldier despite explicit orders that he not be harmed.[9] Upon his tomb is etched a cylinder circumscribing a sphere and the ratio between the volumes of the two bodies.[10]

Only a fraction of the short Kyklou Metresis (Measurement of a Circle) still exists.[11] It consists of three propositions by Archimedes written in the form of a correspondence with Dositheus of Pelusium, a student of Conon of Samos. The work contains a deduction of the constant ratio of a circle's circumference to its diameter.[12] This approximates what we now call the mathematical constant pi (π). Archimedes discovered these bounds on the value of π by inscribing and circumscribing a circle with two similar 96-sided regular polygons.[13]

Evidence for Inclusion in Wythe's Library

See also

References

- ↑ Glen Van Brummelen, The Mathematics of the Heavens and the Earth: The Early History of Trigonometry, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2009), 26.

- ↑ Sherman Stein, Archimedes: What Did He Do Besides Cry Eureka?, (Washington, DC: Mathematical Association of America, 1999), 3.

- ↑ David Frye, "Archimedes' Engines of War," Military History 24, iss. 4 (Oct. 2004): 50.

- ↑ Eduard Jan Dijksterhuis, Archimedes, trans. C. Dikshoorn (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1987), 11.

- ↑ Dijksterhuis, Archimedes, 18-19.

- ↑ Dijksterhuis, Archimedes, 23.

- ↑ Dijksterhuis, Archimedes, 27.

- ↑ Thomas W. Africa, "Archimedes through the Looking-Glass," The Classical World 68, no. 5 (1975): 305.

- ↑ Dijksterhuis, Archimedes, 30-31.

- ↑ Dijksterhuis, Archimedes, 32.

- ↑ Thomas Little Heath, A Manual of Greek Mathematics, (Mineola, N.Y.: Dover Publications, 1931), 146.

- ↑ Heath, A Manual of Greek Mathematics, 146.

- ↑ Heath, A Manual of Greek Mathematics, 146.