Cours de Mathematiques: Difference between revisions

| Line 16: | Line 16: | ||

|pages= | |pages= | ||

|desc=[[:Category:Octavos|8vo]] | |desc=[[:Category:Octavos|8vo]] | ||

}}Étienne Bézout was born in 1730 in Nemours, France, to a family of magistrates.<ref>J. J. O'Connor and E. F. Robertson, “Étienne Bézout," <i>MacTutor History of Mathematics,</i> (University of St. Andrews, Scotland, February 2000).[https://mathshistory.st-andrews.ac.uk/Biographies/Bezout.]</ref> In 1764, he was appointed examiner of the Gardes de la Marine, a position he would hold until his death in 1783.<ref>Monica Blanco Abellán, “The Mathematical Courses of Pedro Padilla and Étienne Bézout: Teaching Calculus in Eighteenth-Century Spain and France,” <i>Science & Education</i> 22, no.4 (2012), 776.</ref> One of his tasks was to write a textbook specifically teaching mathematics, which would later become <i>Cours de Mathematiques, a l'Usage des Gardes du Corps de la Marine.</i><ref>O'Connor and Robertson, "Etienne Bezout."</ref> Bézout also made significant contributions to the field of elimination theory.<ref>Judith Grabiner, "Bezout, Etienne" in <i>Complete Dictionary of Scientific Biography,</i> vol. 2 (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 2008) 111–114.[https://mathshistory.st-andrews.ac.uk/DSB/Bezout.pdf.]</ref> For example, in "Théorie générale des équations algébraiques," published in 1779, Bézout expanded on elimination theory and the symmetric functions of the roots of an algebraic equation.<ref>O'Connor and Robertson, "Etienne Bezout."</ref> He also established what is today known as Bézout's theorem, which states that “the degree of the eliminand of a system a <i>n</i> algebraic equations in <i>n</i> unknowns, when each of the equations is generic of its degree, is the product of the degrees of the equations.”<ref>Erwan Penchèvre, “Etienne Bézout on elimination theory,” arXiv:1606.03711 (2016), 1.</ref> | }}Étienne Bézout was born in 1730 in Nemours, France, to a family of magistrates.<ref>J. J. O'Connor and E. F. Robertson, “Étienne Bézout," <i>MacTutor History of Mathematics,</i> (University of St. Andrews, Scotland, February 2000).[https://mathshistory.st-andrews.ac.uk/Biographies/Bezout.]</ref> In 1764, he was appointed examiner of the Gardes de la Marine, a position he would hold until his death in 1783.<ref>Monica Blanco Abellán, “The Mathematical Courses of Pedro Padilla and Étienne Bézout: Teaching Calculus in Eighteenth-Century Spain and France,” <i>Science & Education</i> 22, no.4 (2012), 776.</ref> One of his tasks was to write a textbook specifically teaching mathematics, which would later become <i>Cours de Mathematiques, a l'Usage des Gardes du Corps de la Marine.</i><ref>O'Connor and Robertson, "Etienne Bezout."</ref> Bézout was known as a savant who was well-regarded in mathematical research circles.<ref>Abellán, "The Mathematical Courses," 784</ref>, a contributing factor to the wide circulation of C<i>ours</i>. He also made significant contributions to the field of elimination theory.<ref>Judith Grabiner, "Bezout, Etienne" in <i>Complete Dictionary of Scientific Biography,</i> vol. 2 (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 2008) 111–114.[https://mathshistory.st-andrews.ac.uk/DSB/Bezout.pdf.]</ref> For example, in "Théorie générale des équations algébraiques," published in 1779, Bézout expanded on elimination theory and the symmetric functions of the roots of an algebraic equation.<ref>O'Connor and Robertson, "Etienne Bezout."</ref> He also established what is today known as Bézout's theorem, which states that “the degree of the eliminand of a system a <i>n</i> algebraic equations in <i>n</i> unknowns, when each of the equations is generic of its degree, is the product of the degrees of the equations.”<ref>Erwan Penchèvre, “Etienne Bézout on elimination theory,” arXiv:1606.03711 (2016), 1.</ref> | ||

<i>Cours de Mathématiques</i> | <i>Cours de Mathématiques</i> was the first work for French military students that contained principles and applications of calculus, and it quickly became a best-seller both nationally and internationally.<ref>Abellán, "The Mathematical Course," 769-70.</ref> <i>Cours</i> was published in six volumes, each focusing on a different topic: (1) elements of arithmetic; (2) elements of geometry, plane and spherical trigonometry; (3) algebra its application to arithmetic and the geometry; (4) general principles of the mechanics along with the principles of calculus; (5) application of the general principles of mechanics; and (6) a treatise on navigation.<ref>Abellán, "The Mathematical Course," 776-7.</ref> When Bézout was appointed examiner of the artillery in 1768 after the death of Charles-Étienne Camus, he reduced and adapted the six volumes of <i>Cours</i> into four volumes specifically intended for artillery students.<ref>Abellán, "The Mathematical Courses," 777.</ref> The various editions of <i>Cours</i> would later became the reference book of candidates for the entrance examination for the Ecole Polytechnique, and it would continue to be reprinted until 1822, circulating not just in French but also in English, Portuguese and Russian.<ref>Abellán, "The Mathematical Course," 777.</ref> The English version was intended specifically for students at Harvard.<ref>O'Connor and Robertson, "Etienne Bezout."</ref> | ||

Pedagogically, <i>Cours</i> contained mandatory information on the basic principles of mathematics, and optional content for higher-level students as well.<ref>Abellán, "The Mathematical Courses," 777.</ref> It contained the study of sine, cosine, logarithmic, and exponential quantities.<ref>Abellán, "The Mathematical Courses," 778.</ref> When teaching calculus, Bézout used the <i>infiniment petits</i> method, or “the infinitely small increments of variable quantities,” an approach which became dominant amongst French engineers in the 1800s.<ref>Abellán, "The Mathematical Courses," 779.</ref> | Pedagogically, <i>Cours</i> contained mandatory information on the basic principles of mathematics, and optional content for higher-level students as well.<ref>Abellán, "The Mathematical Courses," 777.</ref> It contained the study of sine, cosine, logarithmic, and exponential quantities.<ref>Abellán, "The Mathematical Courses," 778.</ref> When teaching calculus, Bézout used the <i>infiniment petits</i> method, or “the infinitely small increments of variable quantities,” an approach which became dominant amongst French engineers in the 1800s.<ref>Abellán, "The Mathematical Courses," 779.</ref> | ||

Revision as of 16:00, 24 October 2025

by Etienne Bézout

| Cours de Mathematiques | ||

at the College of William & Mary. |

||

| Author | Etienne Bézout | |

| Edition | Precise edition unknown. | |

| Desc. | 8vo | |

Étienne Bézout was born in 1730 in Nemours, France, to a family of magistrates.[1] In 1764, he was appointed examiner of the Gardes de la Marine, a position he would hold until his death in 1783.[2] One of his tasks was to write a textbook specifically teaching mathematics, which would later become Cours de Mathematiques, a l'Usage des Gardes du Corps de la Marine.[3] Bézout was known as a savant who was well-regarded in mathematical research circles.[4], a contributing factor to the wide circulation of Cours. He also made significant contributions to the field of elimination theory.[5] For example, in "Théorie générale des équations algébraiques," published in 1779, Bézout expanded on elimination theory and the symmetric functions of the roots of an algebraic equation.[6] He also established what is today known as Bézout's theorem, which states that “the degree of the eliminand of a system a n algebraic equations in n unknowns, when each of the equations is generic of its degree, is the product of the degrees of the equations.”[7]

Cours de Mathématiques was the first work for French military students that contained principles and applications of calculus, and it quickly became a best-seller both nationally and internationally.[8] Cours was published in six volumes, each focusing on a different topic: (1) elements of arithmetic; (2) elements of geometry, plane and spherical trigonometry; (3) algebra its application to arithmetic and the geometry; (4) general principles of the mechanics along with the principles of calculus; (5) application of the general principles of mechanics; and (6) a treatise on navigation.[9] When Bézout was appointed examiner of the artillery in 1768 after the death of Charles-Étienne Camus, he reduced and adapted the six volumes of Cours into four volumes specifically intended for artillery students.[10] The various editions of Cours would later became the reference book of candidates for the entrance examination for the Ecole Polytechnique, and it would continue to be reprinted until 1822, circulating not just in French but also in English, Portuguese and Russian.[11] The English version was intended specifically for students at Harvard.[12]

Pedagogically, Cours contained mandatory information on the basic principles of mathematics, and optional content for higher-level students as well.[13] It contained the study of sine, cosine, logarithmic, and exponential quantities.[14] When teaching calculus, Bézout used the infiniment petits method, or “the infinitely small increments of variable quantities,” an approach which became dominant amongst French engineers in the 1800s.[15]

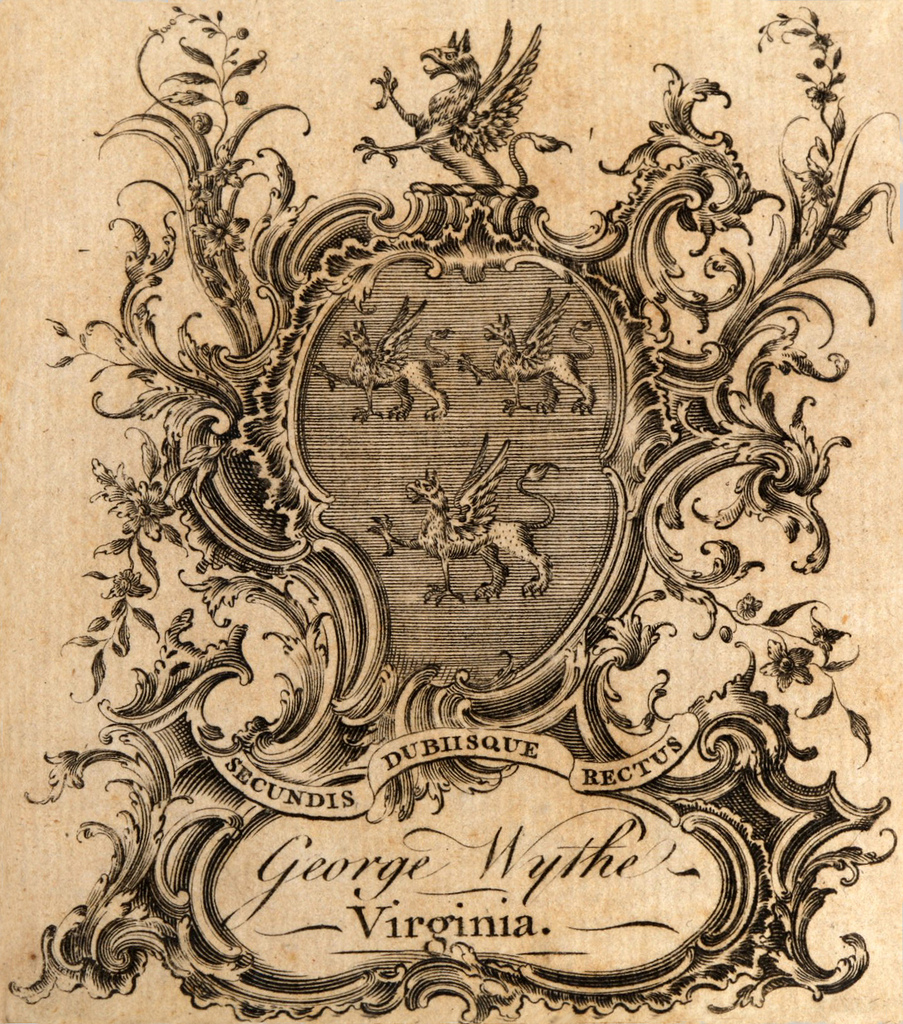

Evidence for Inclusion in Wythe's Library

Listed in the Jefferson Inventory of Wythe's Library as "Mathematiques de Bezout. 3d. & 4th. vols. 8vo." and given by Thomas Jefferson to James Ogilvie, the tutor of Jefferson's grandson Thomas Jefferson Randolph. The precise edition owned by Wythe is unknown. The Brown Bibliography[16] lists either the 1775 or 1781-1784 editions. George Wythe's Library[17] on LibraryThing indicates "Precise edition unknown. Several quarto editions were published at Paris. Jefferson's copy was of the 1781 edition." As yet, the Wolf Law Library has been unable to procure a copy of Cours de Mathematiques.

See also

References

- ↑ J. J. O'Connor and E. F. Robertson, “Étienne Bézout," MacTutor History of Mathematics, (University of St. Andrews, Scotland, February 2000).[1]

- ↑ Monica Blanco Abellán, “The Mathematical Courses of Pedro Padilla and Étienne Bézout: Teaching Calculus in Eighteenth-Century Spain and France,” Science & Education 22, no.4 (2012), 776.

- ↑ O'Connor and Robertson, "Etienne Bezout."

- ↑ Abellán, "The Mathematical Courses," 784

- ↑ Judith Grabiner, "Bezout, Etienne" in Complete Dictionary of Scientific Biography, vol. 2 (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 2008) 111–114.[2]

- ↑ O'Connor and Robertson, "Etienne Bezout."

- ↑ Erwan Penchèvre, “Etienne Bézout on elimination theory,” arXiv:1606.03711 (2016), 1.

- ↑ Abellán, "The Mathematical Course," 769-70.

- ↑ Abellán, "The Mathematical Course," 776-7.

- ↑ Abellán, "The Mathematical Courses," 777.

- ↑ Abellán, "The Mathematical Course," 777.

- ↑ O'Connor and Robertson, "Etienne Bezout."

- ↑ Abellán, "The Mathematical Courses," 777.

- ↑ Abellán, "The Mathematical Courses," 778.

- ↑ Abellán, "The Mathematical Courses," 779.

- ↑ Bennie Brown, "The Library of George Wythe of Williamsburg and Richmond," (unpublished manuscript, May, 2012, rev. 2014) Microsoft Word file. Earlier edition available at: https://digitalarchive.wm.edu/handle/10288/13433

- ↑ LibraryThing, s.v. "Member: George Wythe," accessed on January 28, 2015.