Treatise of Algebra in Three Parts: Difference between revisions

Aevrountas (talk | contribs) |

Aevrountas (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 20: | Line 20: | ||

MacLaurin was a follower and a defender of the ideas of Isaac Newton. His defense of Newton’s calculus, made in response to the attacks made by George Berkeley, brought Maclaurin particular prominence.<ref>O’Connor and Robertson, "Colin Maclaurin."</ref> It is likely that Newton and MacLaurin met in London during MacLaurin’s first visit to London. <ref>O’Connor and Robertson, "Colin Maclaurin."</ref> A recommendation from Newton helped MacLaurin gain his position at the University of Edinburgh.<ref>"Colin Maclaurin," Encyclopedia Britannica, last modified January 28, 2025. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Colin-Maclaurin.</ref> | MacLaurin was a follower and a defender of the ideas of Isaac Newton. His defense of Newton’s calculus, made in response to the attacks made by George Berkeley, brought Maclaurin particular prominence.<ref>O’Connor and Robertson, "Colin Maclaurin."</ref> It is likely that Newton and MacLaurin met in London during MacLaurin’s first visit to London. <ref>O’Connor and Robertson, "Colin Maclaurin."</ref> A recommendation from Newton helped MacLaurin gain his position at the University of Edinburgh.<ref>"Colin Maclaurin," Encyclopedia Britannica, last modified January 28, 2025. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Colin-Maclaurin.</ref> | ||

Maclaurin’s thesis intertwined with many Newtonian ideas. It was centered on the theory of gravity. He did not diverge greatly from Newton’s "observed law of terrestrial gravity" as explanation for "lunar and planetary motion." <ref>Sageng, "MacLaurin, Colin (1698–1746)."</ref> But, his thesis also touched upon the interrelated nature of gravitational forces and divine nature, arguing "that it can only be accounted for as the direct result of divine will."<ref>Sageng, "MacLaurin, Colin (1698–1746)."</ref> After successfully defending his thesis, he remained at the University of Glasgow for one additional year and studied divinity, but he left the school before completing any additional official degree. <ref>Sageng, "MacLaurin, Colin (1698–1746)."</ref> | |||

MacLaurin wrote "A Treatise of Algebra" while teaching at University of Edinburgh. He wrote it to be used in his own courses, but was published officially posthumously.<ref>Sageng, "MacLaurin, Colin (1698-1746)."</ref> It was a popular textbook, and was preprinted in many editions.<ref>Sageng, "MacLaurin, Colin (1698-1746)."</ref> | MacLaurin wrote "A Treatise of Algebra" while teaching at University of Edinburgh. He wrote it to be used in his own courses, but was published officially posthumously.<ref>Sageng, "MacLaurin, Colin (1698-1746)."</ref> It was a popular textbook, and was preprinted in many editions.<ref>Sageng, "MacLaurin, Colin (1698-1746)."</ref> | ||

Revision as of 18:38, 17 October 2025

by Colin MacLaurin

| Treatise of Algebra in Three Parts | ||

at the College of William & Mary. |

||

| Author | Colin MacLaurin | |

| Edition | Precise edition unknown | |

| Desc. | 8vo | |

Scottish mathematician Colin MacLaurin (1698–1746) was born in Kilmoden, Argyll, Scotland, in February of 1698.[1] His father was a minister, and demonstrated academic prowess through his correspondence with American metaphysician Jonathan Edwards.[2] He also portrayed intellectual strength by translating the psalms into Gaelic.[3] MacLaurin’s father died weeks after his birth, and his mother died when he was only nine years old.[4] He moved in with his uncle before beginning at the University of Glasgow at age 11.[5] Throughout his career, MacLaurin held teaching positions at the University of Aberdeen and the University of Edinburgh. He was a fellow of the Royal Society and a winner of the Grand Prize from the Académie des Sciences.

MacLaurin was a follower and a defender of the ideas of Isaac Newton. His defense of Newton’s calculus, made in response to the attacks made by George Berkeley, brought Maclaurin particular prominence.[6] It is likely that Newton and MacLaurin met in London during MacLaurin’s first visit to London. [7] A recommendation from Newton helped MacLaurin gain his position at the University of Edinburgh.[8]

Maclaurin’s thesis intertwined with many Newtonian ideas. It was centered on the theory of gravity. He did not diverge greatly from Newton’s "observed law of terrestrial gravity" as explanation for "lunar and planetary motion." [9] But, his thesis also touched upon the interrelated nature of gravitational forces and divine nature, arguing "that it can only be accounted for as the direct result of divine will."[10] After successfully defending his thesis, he remained at the University of Glasgow for one additional year and studied divinity, but he left the school before completing any additional official degree. [11]

MacLaurin wrote "A Treatise of Algebra" while teaching at University of Edinburgh. He wrote it to be used in his own courses, but was published officially posthumously.[12] It was a popular textbook, and was preprinted in many editions.[13]

This treatise of algebra includes a breakdown of basic algebraic formulas.[14] An instruction manual for schooling, this text also focuses on the application of algebra and geometry to each other and an Appendix containing the basic principles of geometrical lines.[15] Clarity and simplicity were the main goals of this volume in distilling the more abstruse theorems into a simple presentation.[16]

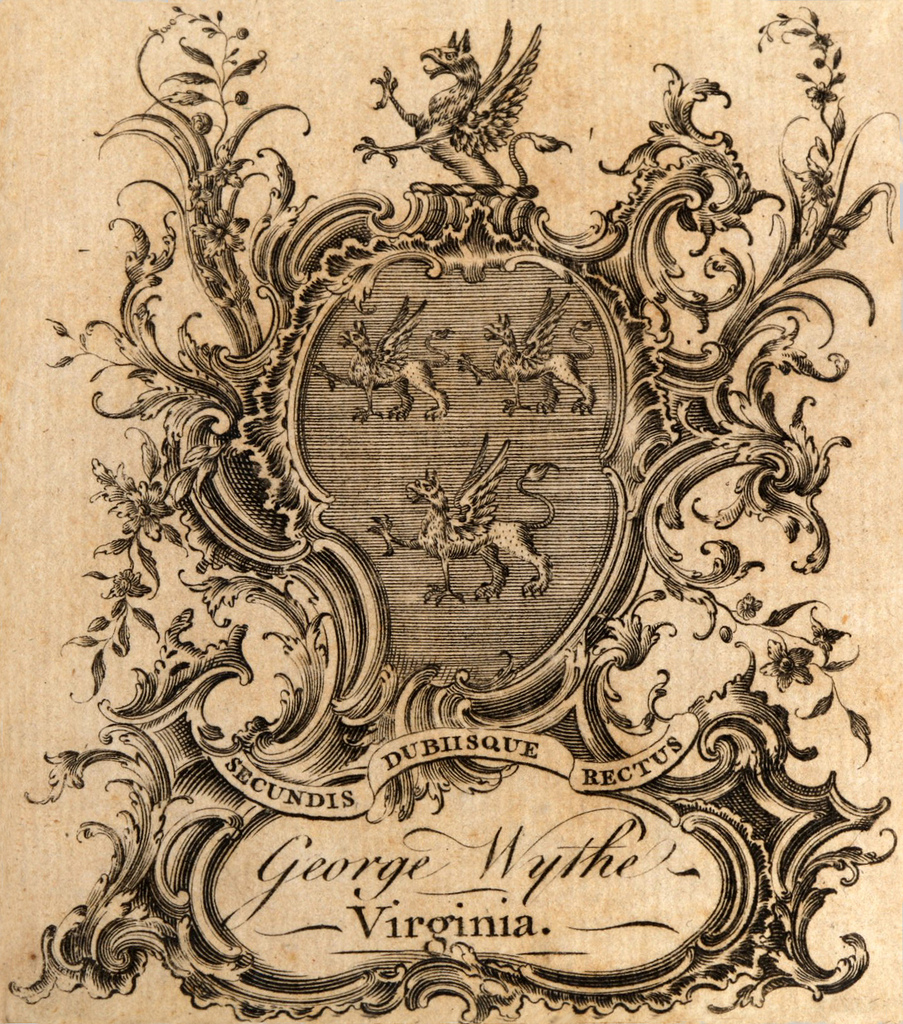

Evidence for Inclusion in Wythe's Library

Listed in the Jefferson Inventory of Wythe's Library as "Mc.laurin's Algebra. 8vo." and given by Thomas Jefferson to his grandson Thomas Jefferson Randolph. The Brown Bibliography[17] lists the first edition published in London in 1748. George Wythe's Library[18] on LibraryThing states "Precise edition unknown. Octavo editions were published in 1748, 1756, 1771, 1779, 1788, and 1796." The Wolf Law Library has yet to purchase a copy of McLaurin's Treatise of Algebra.

See also

References

External Links

- ↑ Erik Lars Sageng, "MacLaurin, Colin (1698–1746)" in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, accessed March 25, 2025.

- ↑ J O'Connor and E F Robertson, "Colin Maclaurin," School of Mathematics and Statistics, University of St Andrews, Scotland, last modified May 2017, https://mathshistory.st-andrews.ac.uk/Biographies/Maclaurin/

- ↑ O’Connor and Robertson, "Colin Maclaurin."

- ↑ O’Connor and Robertson, "Colin Maclaurin."

- ↑ O’Connor and Robertson, "Colin Maclaurin."

- ↑ O’Connor and Robertson, "Colin Maclaurin."

- ↑ O’Connor and Robertson, "Colin Maclaurin."

- ↑ "Colin Maclaurin," Encyclopedia Britannica, last modified January 28, 2025. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Colin-Maclaurin.

- ↑ Sageng, "MacLaurin, Colin (1698–1746)."

- ↑ Sageng, "MacLaurin, Colin (1698–1746)."

- ↑ Sageng, "MacLaurin, Colin (1698–1746)."

- ↑ Sageng, "MacLaurin, Colin (1698-1746)."

- ↑ Sageng, "MacLaurin, Colin (1698-1746)."

- ↑ A Treatise of Algebra: In Three Parts. Containing : Colin MacLaurin : Free Download & Streaming : Internet Archive (Internet Archive) https://archive.org/details/atreatisealgebr03maclgoog

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Bennie Brown, "The Library of George Wythe of Williamsburg and Richmond," (unpublished manuscript, 2009, rev. 2023) Microsoft Word document (on file at the Wolf Law Library, William & Mary Law School).

- ↑ LibraryThing, s.v. "Member: George Wythe," accessed on July 10, 2025.

Read the 1748 edition of this book in Google Books.